Menachem Binyamin Zivotofsky v. John Kerry, Secretary of State

Certiorari granted by the United States Supreme Court on April 21, 2014 Oral arguments scheduled TBD

Outline:

The Parties

| Petitioner: Menachem Binyamin Zivotofsky, by his parents and guardians Ari Z. and Naomi Siegman Zivotofsky |

v. |

Respondent: John Kerry, Secretary of State |

(jump to the top of the page)

The Questions Presented

- What is the recognition power?

- What is the scope of that Power?

- Who holds that power, the President, Congress, or both?

- Is the president’s recognition power subject to laws enacted by congress?

- Whether a congressionally enacted statute that directs the Secretary of State, upon request, to record the birthplace of an American citizen born in Jerusalem as born in “Israel” on a Consular Report of Birth Abroad and on a United States passport is unconstitutional on the ground that the statute “impermissibly infringes on the President’s exercise of the recognition power?”

(jump to the top of the page)

Case Background

[caption id="attachment_2313" align="alignright" width="300"] American Embassy in Tel Aviv, Israel not Jerusalem[/caption]

For the last 60 years, the President of the United States, acting through his Secretary of State, has recognized no country as having control over the city of Jerusalem, even though the city resides in the country of Israel. As part of this policy, the passports of American citizens who are born in Jerusalem list their country of birth as Jerusalem, rather than Israel. This is so even though Jerusalem is not actually a country, but a city.

In 2002, Congress passed a law mandating that the Secretary of State should, upon the request of citizens born in Jerusalem or their legal guardians, list the place of birth as Israel on their passport.

American Embassy in Tel Aviv, Israel not Jerusalem[/caption]

For the last 60 years, the President of the United States, acting through his Secretary of State, has recognized no country as having control over the city of Jerusalem, even though the city resides in the country of Israel. As part of this policy, the passports of American citizens who are born in Jerusalem list their country of birth as Jerusalem, rather than Israel. This is so even though Jerusalem is not actually a country, but a city.

In 2002, Congress passed a law mandating that the Secretary of State should, upon the request of citizens born in Jerusalem or their legal guardians, list the place of birth as Israel on their passport.

Menachem, Ari, and Naomi ZivotofskySecretary of State John Kerry, the Respondent,, acting on behalf of the President, argues that the Constitution assigns to the President alone the recognition power to recognize foreign states or governments. The President alone can decide whether to recognize Israel as the country with control, or sovereignty, over the city of Jerusalem. Congress cannot pass laws that limit the President’s recognition power.

In contrast, Petitioner Zivotofsky, argues that the historical evidence establishes that the President’s recognition power is subject to laws enacted by the U.S. Congress, like the one discussed above. Zivotofsky wants the State Department to list his son’s country of birth as “Israel,” and not “Jerusalem.”

Alexander Hamilton[/caption]

(2) The Federalist No. 69 (Alexander Hamilton)

Alexander Hamilton[/caption]

(2) The Federalist No. 69 (Alexander Hamilton)

Thomas Jefferson[/caption]

(4) Thomas Jefferson, Opinion on the Powers of the Senate Respecting Diplomatic Appointments

Thomas Jefferson[/caption]

(4) Thomas Jefferson, Opinion on the Powers of the Senate Respecting Diplomatic Appointments

St. George Tucker[/caption]

(5) 1 St. George Tucker, Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference to the Constitution and Laws of the Federal Government of the United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Appendix Note D (1803)

St. George Tucker[/caption]

(5) 1 St. George Tucker, Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference to the Constitution and Laws of the Federal Government of the United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Appendix Note D (1803)

William Rawle[/caption]

(6) William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States, Chapter XX (1829)

William Rawle[/caption]

(6) William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States, Chapter XX (1829)

Joseph Story[/caption]

(7) Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §§1560-62 (1833)

Joseph Story[/caption]

(7) Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §§1560-62 (1833)

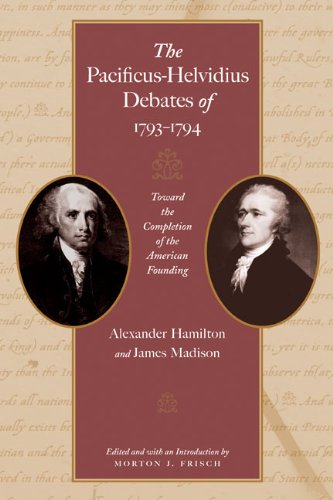

(8) Pacificus No. 1 (Alexander Hamilton) (1793)

(8) Pacificus No. 1 (Alexander Hamilton) (1793)

James Madison, as Helvidius[/caption]

(9) Helvidius No. 3 (James Madison) (1793)

James Madison, as Helvidius[/caption]

(9) Helvidius No. 3 (James Madison) (1793)

George Washington[/caption]

(10) Early Debates over Recognition in the First Presidential Administrations

Please research the following debates over the President’s recognition power during the first three presidential administrations.

To research the congressional debates, we recommend using: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/

To research the president’s records, we recommend using: www.founders.archives.gov

George Washington[/caption]

(10) Early Debates over Recognition in the First Presidential Administrations

Please research the following debates over the President’s recognition power during the first three presidential administrations.

To research the congressional debates, we recommend using: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/

To research the president’s records, we recommend using: www.founders.archives.gov

The Law

THE RECOGNITION POWER

According to RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF FOREIGN RELATIONS §94(1), “Recognition” is the act by which “a state commits itself to treat an entity as a state or to treat a regime as the government of a state.” Recognition is an important step in establishing diplomatic relations with the United States. If the U.S. does not recognize a state, it means the U.S. is “unwilling[] to acknowledge that the government in question speaks as the sovereign authority for the territory it purports to control.” Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376. U.S. 398 (1964).THE CONSTITUTION

The Constitution distributes the powers of the national government over foreign relations primarily between the Executive and Legislative branches.Article I

The following clauses in Article I of the Constitution describe the powers granted to Congress over foreign relations:Article I, §8, Cl. 3: The Congress shall have the Power To regulate Commerce with foreign nations[.] Article I, §8, Cl. 5: The Congress shall have the Power To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standards of Weights and Measures[.] Article I, §8, Cl. 10: The Congress shall have the Power To define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations[.] Article I, §8, Cl. 11: The Congress shall have the Power to declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water[.]Guiding Question: What is the relationship, if any, between the power to receive ambassadors, and the recognition power?

Article II

The following clauses in Article II of the Constitution describe the powers granted to the President over foreign relations:Article II, §2, Cl. 1: The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States[.] Article II, §2, Cl. 2: [The President] shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors[.] Article II, §3: [The President] shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers[.]Guiding Question: Does any clause in the Constitution expressly grant to either Congress or the President the recognition power? If not, where does this power come from?

Primary Sources - The History

Read the following excerpts from important historical treatises, articles, speeches, and letters, and construct an argument that the text and history of the Constitution supports either the petitioner or the government. Consider whether the history supports the side of Zivotofsky (Petitioner) or Kerry (Respondent). (1) The Articles of Confederation, Art. IX (1781)The United States in Congress assembled, shall have the sole and exclusive right and power…of sending and receiving ambassadors.Guiding Question: What powers, if any, did the President have over foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation? [caption id="attachment_2316" align="alignright" width="149"]

Alexander Hamilton[/caption]

(2) The Federalist No. 69 (Alexander Hamilton)

Alexander Hamilton[/caption]

(2) The Federalist No. 69 (Alexander Hamilton)

The President is also to be authorized to receive ambassadors and other public ministers. This, though it has been a rich theme of declamation, is more a matter of dignity than of authority. It is a circumstance which will be without consequence in the administration of the government; and it was far more convenient that it should be arranged in this manner, than that there should be a necessity of convening the legislature, or one of its branches, upon every arrival of a foreign minister, though it were merely to take the place of a departed predecessor.Guiding Question: What does it mean for the power to be “more a matter of dignity than of authority?” (3) Statement of Archibald Maclaine in the North Carolina Ratifying Convention (July 28, 1788)

It has been objected to this part, that the power of appointing officers was something like a monarchical power. Congress are not to be sitting at all times; they will only sit from time to time, as the public business may render it necessary. Therefore the executive ought to make temporary appointments, as well as receive ambassadors and other public ministers. This power can be vested nowhere but in the executive, because he is perpetually acting for the public; for, though the Senate is to advise him in the appointment of officers, &c., yet, during the recess, the President must do this business, or else it will be neglected; and such neglect may occasion public inconveniences.Guiding Questions: Why would the power to receive ambassadors be exclusive to the President? [caption id="attachment_2317" align="alignright" width="157"]

Thomas Jefferson[/caption]

(4) Thomas Jefferson, Opinion on the Powers of the Senate Respecting Diplomatic Appointments

Thomas Jefferson[/caption]

(4) Thomas Jefferson, Opinion on the Powers of the Senate Respecting Diplomatic Appointments

The transaction of business with foreign nations is Executive altogether. It belongs then to the head of that department, except as to such portions of it as are specially submitted to the Senate. Exceptions are to be construed strictly. The Constitution itself indeed has taken care to circumscribe this one within very strict limits: for it gives the nomination of the foreign Agent to the President, the appointment to him and the Senate jointly, the commissioning to the President. This analysis calls our attention to the strict import of each term. To nominate must be to propose: appointment seems that act of the will which constitutes or makes the Agent: and the Commission is the public evidence of it. But there are still other acts previous to these, not specially enumerated in the Constitution; to wit 1. the destination of a mission to the particular country where the public service calls for it: and 2. the character, or grade to be employed in it. The natural order of all these is 1. destination. 2. grade. 3. nomination. 4. appointment. 5. commission. If appointment does not comprehend the neighboring acts of nomination, or commission, (and the constitution says it shall not, by giving them exclusively to the President) still less can it pretend to comprehend those previous and more remote of destination and grade. The Constitution, analysing the three last, shews they do not comprehend the two first. The 4th. is the only one it submits to the Senate, shaping it into a right to say that "A. or B. is unfit to be appointed." Now this cannot comprehend a right to say that "A. or B. is indeed fit to be appointed, but the grade fixed on is not the fit one to employ," or "our connections with the country of his destination are not such as to call for any mission." The Senate is not supposed by the Constitution to be acquainted with the concerns of the Executive department. It was not intended that these should be communicated to them; nor can they therefore be qualified to judge of the necessity which calls for a mission to any particular place, or of the particular grade, more or less marked, which special and secret circumstances may call for. All this is left to the President. They are only to see that no unfit person be employed.Guiding Question: What role does Jefferson see for the Senate in matters involving foreign nations? If a specific function—such as the recognition—is not clearly assigned to the President or the Congress, who would Jefferson give it to? [caption id="attachment_2318" align="alignright" width="132"]

St. George Tucker[/caption]

(5) 1 St. George Tucker, Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference to the Constitution and Laws of the Federal Government of the United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Appendix Note D (1803)

St. George Tucker[/caption]

(5) 1 St. George Tucker, Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference to the Constitution and Laws of the Federal Government of the United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Appendix Note D (1803)

The president, alone, has authority to receive foreign ministers; a power of some importance, as it may sometimes involve in the exercise of it, questions of delicacy; especially in the recognition of authorities of a doubtful nature. A scruple is said to have been entertained by the president of the United States, as to the reception of the first ambassador from the French republic. But it did not prevent, or retard his reception, in that character.... These powers are respectively branches of the royal prerogative in England.Guiding Question: What are the “questions of delicacy” involved in the “recognition of authorities of a doubtful nature”? [caption id="attachment_2319" align="alignright" width="188"]

William Rawle[/caption]

(6) William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States, Chapter XX (1829)

William Rawle[/caption]

(6) William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States, Chapter XX (1829)

1. But it is in respect to external relations; to transactions with foreign nations, and the events arising from them, that the president has an arduous task. Here he must chiefly act on his own independent judgment. 2. The power of receiving foreign ambassadors, carries with it among other things, the right of judging in the case of a revolution in a foreign country, whether the new rulers ought to be recognised [sic]. The legislature indeed possesses a superior power, and may declare its dissent from the executive recognition or refusal, but until that sense is declared, the act of the executive is binding. 3. The power of congress on this subject cannot be controlled; they may, if they think proper, acknowledge a small and helpless community, though with a certainty of drawing a war upon our country; but greater circumspection is required from the president, who, not having the constitutional power to declare war, ought ever to abstain from a measure likely to produce it.Guiding Question: What are the difficulties of recognizing a country “in the case of a revolution?” What is the legislature’s “superior power” with respect to recognition? How can Congress “Declare its dissent from the executive recognition”? [caption id="attachment_2320" align="alignright" width="177"]

Joseph Story[/caption]

(7) Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §§1560-62 (1833)

Joseph Story[/caption]

(7) Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §§1560-62 (1833)

§ 1560. The power to receive ambassadors and ministers is always an important, and sometimes a very delicate function; since it constitutes the only accredited medium, through which negotiations and friendly relations are ordinarily carried on with foreign powers. A government may in its discretion lawfully refuse to receive an ambassador, or other minister, without its affording any just cause of war. But it would generally be deemed an unfriendly act, and might provoke hostilities, unless accompanied by conciliatory explanations. A refusal is sometimes made on the ground of the bad character of the minister, or his former offensive conduct, or of the special subject of the embassy not being proper, or convenient for discussion. This, however, is rarely done. But a much more delicate occasion is, when a civil war breaks out in a nation, and two nations are formed, or two parties in the same nation, each claiming the sovereignty of the whole, and the contest remains as yet undecided, flagrante bello. In such a case a neutral nation may very properly withhold its recognition of the supremacy of either party, or of the existence of two independent nations; and on that account refuse to receive an ambassador from either. It is obvious, that in such cases the simple acknowledgment of the minister of either party, or nation, might be deemed taking part against the other; and thus as affording a strong countenance, or opposition, to rebellion and civil dismemberment. On this account, nations, placed in such a predicament, have not hesitated sometimes to declare war against neutrals, as interposing in the war; and have made them the victims of their vengeance, when they have been anxious to assume a neutral position. The exercise of this prerogative of acknowledging new nations, or ministers, is, therefore, under such circumstances, an executive function of great delicacy, which requires the utmost caution and deliberation. If the executive receives an ambassador, or other minister, as the representative of a new nation, or of a party in a civil war in an old nation, it is an acknowledgment of the sovereign authority de facto of such new nation, or party. If such recognition is made, it is conclusive upon the nation, unless indeed it can be reversed by an act of congress repudiating it. If, on the other hand, such recognition has been refused by the executive, it is said, that congress may, notwithstanding, solemnly acknowledge the sovereignty of the nation, or party. These, however, are propositions, which have hitherto remained, as abstract statements, under the constitution; and, therefore, can be propounded, not as absolutely true, but as still open to discussion, if they should ever arise in the course of our foreign diplomacy. The constitution has expressly invested the executive with power to receive ambassadors, and other ministers. It has not expressly invested congress with the power, either to repudiate, or acknowledge them. At all events, in the case of a revolution, or dismemberment of a nation, the judiciary cannot take notice of any new government, or sovereignty, until it has been duly recognised by some other department of the government, to whom the power is constitutionally confided.Guiding Question: Following a civil war, where two governments claim power in a nation, how should the United States decide which government is to be recognized? What role does the President’s power to receive ambassadors play in the recognition function? What happens if the President and Congress disagree? How can Congress repudiate the President’s recognition?

§ 1561. That a power, so extensive in its reach over our foreign relations, could not be properly conferred on any other, than the executive department, will admit of little doubt. That it should be exclusively confided to that department, without any participation of the senate in the functions, (that body being conjointly entrusted with the treaty-making power,) is not so obvious. Probably the circumstance, that in all foreign governments the power was exclusively confided to the executive department, and the utter impracticability of keeping the senate constantly in session, and the suddenness of the emergencies, which might require the action of the government, conduced to the establishment of the authority in its present form. It is not, indeed, a power likely to be abused; though it is pregnant with consequences, often involving the question of peace and war. And, in our own short experience, the revolutions in France, and the revolutions in South America, have already placed us in situations, to feel its critical character, and the necessity of having, at the head of the government, an executive of sober judgment, enlightened views, and firm and exalted patriotism.Guiding Question: What is the advantage of having a single Executive in charge of recognizing foreign powers, over the Senate as a body sharing this important power?

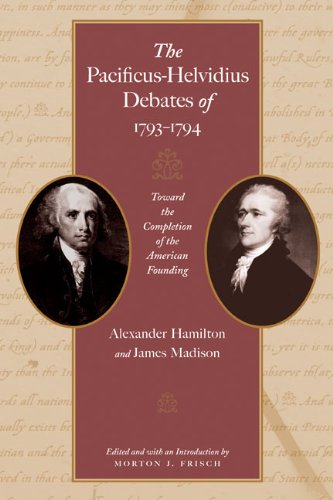

§ 1562. As incidents to the power to receive ambassadors and foreign ministers, the president is understood to possess the power to refuse them, and to dismiss those who, having been received, become obnoxious to censure, or unfit to be allowed the privilege, by their improper conduct, or by political events. While, however, they are permitted to remain, as public functionaries, they are entitled to all the immunities and rights, which the law of nations has provided at once for their dignity, their independence, and their inviolability.Note on the Pacificus-Helvidius Debates: One of the earliest debates on foreign policy appeared in a series of anonymous essays between Pacificus and Helvidius, who responded to each other. We would later learn that Pacificus was actually Alexander Hamilton. Helvidius was actually James Madison.

(8) Pacificus No. 1 (Alexander Hamilton) (1793)

(8) Pacificus No. 1 (Alexander Hamilton) (1793)

The Legislative Department is not the organ of intercourse between the United States and foreign Nations. It is charged neither with making nor interpreting Treaties. It is therefore not naturally that Organ of the Government which is to pronounce the existing condition of the Nation, with regard to foreign Powers, or to admonish the Citizens of their obligations and duties as founded upon that condition of things. Still less is it charged with enforcing the execution and observance of these obligations and those duties. The general doctrine then of our constitution is, that the Executive Power of the Nation is vested in the President; subject only to the exceptions and qu[a]lifications which are expressed in the instrument. Two of these have been already noticed--the participation of the Senate in the appointment of Officers and the making of Treaties. A third remains to be mentioned the right of the Legislature "to declare war and grant letters of marque and reprisal." With these exceptions the Executive Power of the Union is completely lodged in the President. This mode of construing the Constitution has indeed been recognized by Congress in formal acts, upon full consideration and debate. . . . The right of the Executive to receive ambassadors and other public Ministers may serve to illustrate the relative duties of the Executive and Legislative Departments. This right includes that of judging, in the case of a Revolution of Government in a foreign Country, whether the new rulers are competent organs of the National Will and ought to be recognised or not: And where a treaty antecedently exists between the UStates and such nation that right involves the power of giving operation or not to such treaty. For until the new Government is acknowleged, the treaties between the nations, as far at least as regards public rights, are of course suspended. This power of determining virtually in the case supposed upon the operation of national Treaties as a consequence, of the power to receive ambassadors and other public Ministers, is an important instance of the right of the Executive to decide the obligations of the Nation with regard to foreign Nations. To apply it to the case of France, if there had been a Treaty of alliance offensive and defensive between the UStates and that Country, the unqualified acknowlegement of the new Government would have put the UStates in a condition to become an associate in the War in which France was engaged--and would have laid the Legislature under an obligation, if required, and there was otherwise no valid excuse, of exercising its power of declaring war.Guiding Questions: If the Constitution does not grant the recognition power to Congress, to whom would Hamilton give that power? To Hamilton, what is the relationship between the right of receiving ambassadors, and the recognition power? [caption id="attachment_2322" align="alignright" width="175"]

James Madison, as Helvidius[/caption]

(9) Helvidius No. 3 (James Madison) (1793)

James Madison, as Helvidius[/caption]

(9) Helvidius No. 3 (James Madison) (1793)

The words of the constitution are, "He (the president) shall receive ambassadors, other public ministers, and consuls." I shall not undertake to examine, what would be the precise extent and effect of this function in various cases which fancy may suggest, or which time may produce. It will be more proper to observe, in general, and every candid reader will second the observation, that little, if any thing, more was intended by the clause, than to provide for a particular mode of communication, almost grown into a right among modern nations; by pointing out the department of the government, most proper for the ceremony of admitting public ministers, of examining their credentials, and of authenticating their title to the privileges annexed to their character by the law of nations. This being the apparent design of the constitution, it would be highly improper to magnify the function into an important prerogative, even where no rights of other departments could be affected by it.Guiding Question: To Madison, what is the scope of the power to receive ambassadors? Does it entail a recognition power?

To show that the view here given of the clause is not a new construction, invented or strained for a particular occasion--I will take the liberty of recurring to the contemporary work already quoted, which contains the obvious and original gloss put on this part of the constitution by its friends and advocates. "The president is also to be authorized to receive ambassadors and other public ministers. This, though it has been a rich theme of declamation, is more a matter of dignity than of authority. It is a circumstance, that will be without consequence in the administration of the government, and it is far more convenient that it should be arranged in this manner, than that there should be a necessity for convening the legislature or one of its branches upon every arrival of a foreign minister, though it were merely to take the place of a departed predecessor." Fed., No. 69 p. 389.3Guiding Question: Why is it ironic, in responding Pacificus No.1, that Madison is quoting from Federalist No. 69? Hint: Who wrote Pacificus No. 1? Who wrote Federalist No. 69?

Had it been foretold in the year 1788, when this work was published, that before the end of the year 1793, a writer, assuming the merit of being a friend to the constitution, would appear, and gravely maintain, that this function, which was to be without consequence in the administration of the government, might have the consequence of deciding on the validity of revolutions in favour of liberty, "of putting the United States in a condition to become an associate in war"--nay, "of laying the legislature under an obligation of declaring war," what would have been thought and said of so visionary a prophet? The moderate opponents of the constitution would probably have disowned his extravagance. By the advocates of the constitution, his prediction must have been treated as "an experiment on public credulity, dictated either by a deliberate intention to deceive, or by the overflowings of a zeal too intemperate to be ingenuous." But how does it follow from the function to receive ambassadors and other public ministers, that so consequential a prerogative may be exercised by the executive? When a foreign minister presents himself, two questions immediately arise: Are his credentials from the existing and acting government of his country? Are they properly authenticated? These questions belong of necessity to the executive; but they involve no cognizance of the question, whether those exercising the government have the right along with the possession. This belongs to the nation, and to the nation alone, on whom the government operates. The questions before the executive are merely questions of fact; and the executive would have precisely the same right, or rather be under the same necessity of deciding them, if its function was simply to receive without any discretion to reject public ministers. It is evident, therefore, that if the executive has a right to reject a public minister, it must be founded on some other consideration than a change in the government, or the newness of the government; and consequently a right to refuse to acknowledge a new government cannot be implied by the right to refuse a public minister.Guiding Question: To Madison, what is the scope of the President’s power to receive ambassadors? Which branch of government decides whether or not to recognize another government?

It is not denied that there may be cases in which a respect to the general principles of liberty, the essential rights of the people, or the overruling sentiments of humanity, might require a government, whether new or old, to be treated as an illegitimate despotism. Such are in fact discussed and admitted by the most approved authorities. But they are great and extraordinary cases, by no means submitted to so limited an organ of the national will as the executive of the United States; and certainly not to be brought by any torture of words, within the right to receive ambassadors. That the authority of the executive does not extend to a question, whether an existing government ought to be recognised or not, will still more clearly appear from an examination of the next inference of the writer, to wit: that the executive has a right to give or refuse activity and operation to preexisting treaties. If there be a principle that ought not to be questioned within the United States, it is, that every nation has a right to abolish an old government and establish a new one. This principle is not only recorded in every public archive, written in every American heart, and sealed with the blood of a host of American martyrs; but is the only lawful tenure by which the United States hold their existence as a nation. It is a principle incorporated with the above, that governments are established for the national good, and are organs of the national will. From these two principles results a third, that treaties formed by the government, are treaties of the nation, unless otherwise expressed in the treaties.Guiding Question: What is the relationship between the Senate’s power in ratifying treaties, and recognizing foreign countries?

Another consequence is, that a nation, by exercising the right of changing the organ of its will, can neither disengage itself from the obligations, nor forfeit the benefits of its treaties. This is a truth of vast importance, and happily rests with sufficient firmness, on its own authority… As a change of government then makes no change in the obligations or rights of the party to a treaty, it is clear that the executive can have no more right to suspend or prevent the operation of a treaty, on account of the change, than to suspend or prevent the operation, where no such change has happened. Nor can it have any more right to suspend the operation of a treaty in force as a law, than to suspend the operation of any other law.Guiding Question: Can the President suspend the enforcement of a treaty if he decides to no longer recognize that government in charge of that country?

The logic employed by the writer on this occasion, will be best understood by accommodating to it the language of a proclamation, founded on the prerogative and policy of suspending the treaty with France. … The writer, as if beginning to feel that he was grasping at more than he could hold, endeavours all of a sudden to squeeze his doctrine into a smaller size, and a less vulnerable shape. The reader shall see the operation in his own words. "And where a treaty antecedently exists between the United States and such nation, [a nation whose government has undergone a revolution,] that right [the right of judging, whether the new rulers ought to be recognised or not] involves the power of giving operation or not to such treaty. For until the new government is acknowledged, the treaties between the nations as far at least as regards public rights, are of course suspended."Guiding Question: What is the relationship between treaties and the recognition power? [caption id="attachment_2323" align="alignright" width="175"]

George Washington[/caption]

(10) Early Debates over Recognition in the First Presidential Administrations

Please research the following debates over the President’s recognition power during the first three presidential administrations.

To research the congressional debates, we recommend using: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/

To research the president’s records, we recommend using: www.founders.archives.gov

George Washington[/caption]

(10) Early Debates over Recognition in the First Presidential Administrations

Please research the following debates over the President’s recognition power during the first three presidential administrations.

To research the congressional debates, we recommend using: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/

To research the president’s records, we recommend using: www.founders.archives.gov

- President Washington’s recognition of France in 1795.

- President Adams’s recognition of Santo Domingo in 1800.

- President Jefferson’s recognition of St. Domingue in 1806.

(jump to the top of the page)

Tournament Instructions

Resolved: Is the President’s recognition power subject to control by the Congress? Using historical materials related to the recognition power, write an appellate brief arguing whether history does, or does not support the Congress’s power to control the President’s decision not to recognize Jerusalem as part of Israel. Further, also address what the scope is of Congress’s power over recognition. In writing your brief, consider the guiding questions mentioned above. Teams of two high school students will be responsible for writing an appellate brief on their class’s FantasySCOTUS blog. The Petitioner will argue on behalf of Zivotofsky that Congress can force the President to recognize that Jerusalem is part of Israel. The Respondent will argue on behalf of Secretary of State John Kerry that the President alone decides whether or not to recognize a country, and Congress’s statute is unconstitutional. The brief should have the following sections:- Table of Cited Authorities: List all of the original sources, and other documents you cite in your brief.

- Statement of Argument: State your position succinctly in 250 words or less.

- Argument: By relying on the history sources in this lesson plan, structure an argument about the scope of the President’s and Congress’s recognition power. The more authorities you cite, the stronger your argument will be–and the more likely your team will advance.

- Conclusion: Summarize your argument, and argue how the Supreme Court should decide Zivotofsky v. Kerry.