Introduction

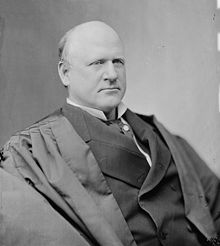

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="220"] Justice John Marshall Harlan[/caption]

This term, the Supreme Court will consider the case of Fisher v. University of Texas. The Harlan Institue has created a lesson plan for this case here. This case presents the question of whether, under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the University of Texas can use race as a factor when making admission decisions. One of the primary arguments against the school granting favorable admission policies to certain minority students is the theory that our Constitution is “color-blind.” Justice John Marshall Harlan, in his famous dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, stated that

Justice John Marshall Harlan[/caption]

This term, the Supreme Court will consider the case of Fisher v. University of Texas. The Harlan Institue has created a lesson plan for this case here. This case presents the question of whether, under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the University of Texas can use race as a factor when making admission decisions. One of the primary arguments against the school granting favorable admission policies to certain minority students is the theory that our Constitution is “color-blind.” Justice John Marshall Harlan, in his famous dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, stated that

Harlan’s “color-blind” vision of the Constitution seems to be in tension with the practice of affirmative action, which bases admission to schools, in part, on a person’s race. Schools that employ race-based affirmative action are not being “color-blind.” Resolved: Is the Fourteenth Amendment Color-Blind? Using historical materials related to the Fourteenth Amendment and reconstruction-era legislation, in addition to cases of the United States Supreme Court, write an appellate brief arguing whether history does, or does not support Harlan’s “color-blind” view of the Constitution.Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 559 (1896).

Instructions

Please see the rules of the Virtual Supreme Court competition. Teams of two high school students will be responsible for writing an appellate brief on their class's FantasySCOTUS blog. The Petitioner will argue that the 14th Amendment is colorblind, and the state cannot make any classifications based on race. The Respondent will argue that the 14th Amendment is not colorblind, and the state can make classifications based on race to promote certain societal objectives. The brief should take either side of the issue of whether the 14th Amendment is colorblind. The brief should have the following sections:- Table of Cited Authorities: List all of the Supreme Court cases, original sources, and other documents you cite in your brief.

- Statement of Argument: State your position succinctly in 250 words or l ess.

- Argument: By relying on the Supreme Court cases discussed in this lesson plan and in this report created by The Constitutional Sources Project (ConSource), and the historical resources included below, structure an argument about whether the 14th Amendment is color-blind or not. In writing the Argument Section of the brief, we recommend you resources discussed on this page. The more authorities you cite, the stronger your argument will be--and the more likely your team will advance.

- Conclusion: Summarize your argument, and argue how the Supreme Court should decide Fisher v. University of Texas.

Resources

For additional historical materials related to the questions listed below, please see ConSource's long-form guide to Fisher v. UT-Austin.I. What does the text of the Fourteenth Amendment suggest about a “color-blind” constitution?

Text: All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

II. Do the Freedmen Bureau Acts support Harlan’s notion of a color-blind constitution?

(1) Freedmen’s Bureau Act, March 3, 1865:

SEC. 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That there is hereby established in the War Department, to continue during the present war of rebellion, and for one year thereafter, a bureau of refugees, freedmen, and abandoned lands, to which shall be committed, as hereinafter provided, the supervision and management of all abandoned lands, and the control of all the subjects relating to refugees and freedmen from rebel states, and from any district of country within the territory embraced in the operations of the army, under such rules and regulations as may be prescribed by the head of the bureau and approved by the President.

SEC. 2. And be it further enacted, That the Secretary of War may direct such issues of provisions, clothing, and fuel, as he may deem needful for the immediate and temporary shelter and supply of destitute and suffering refugees and freedmen and their wives and children, under such rules and regulations as he may direct.

Background: The Freedmen’s Bureau was proposed by President Lincoln at the end of the Civil War and passed by the Thirty-ninth Congress in March 1866. The Bureau provided temporary relief and assistance to freed slaves, war refugees, and other impoverished citizens. For instance, it provided health care to those without the financial means to purchase it, and established courts where freedmen could bring complains of discrimination. The Bureau also helped to facilitate the hiring of freedmen through the drafting of employment contract. The Bureau’s most successful efforts were those to educate newly freed slaves in schools and universities build especially for freedmen.

(2) Act of July 25, 1868, ch. 245, §2:

And be it further enacted, That the commissioner of the bureau shall, on the first day of January next [1869] cause said bureau to be withdrawn from the several State within which said bureau has acted and its operations shall be discontinued. But the educational department of the said bureau . . . shall be continued as now provided by law until otherwise ordered by act of Congress.

Background: The Act of July 25, 1868 required that by January 1869, most Bureau activities were to stop, with the exception of educational efforts. The Educational Department of the Bureau was intended to continue indefinitely as a separate entity. The Department eventually ran out of money and stopped operating in March of 1871.

III. Look at the debates surrounding the Freedmen’s Bureau Act and decide whether they provide support for the idea of a “color-blind” constitution.

(1) Report from the American Freedmen’s Inquiry to the Secretary of War (May 15, 1864)

The sum of our recommendations is this: Offer the freedmen temporary aid and counsel until they become a little accustomed to their new sphere of life; secure to them, by law, their just rights of person and property; relieve them, by a fair and equal administration of justice, from the depressing influence of disgraceful prejudice; above all, guard them against the virtual restoration of slavery in any form, under any pretext, and then let them take care of themselves.

Background: The American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission was created in 1863 by the Secretary of War to investigate both the best manner to protect the newly freed slaves and to provide the temporary assistance necessary to improve their condition. The findings of the Commission helped to guide the actions of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

(2) Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 2799 (1865) (Remarks of Senator Sumner):

It is evident, then, that the freedmen are not idler. They desire work. But in their helpless condition they have not the ability to obtain it without assistance. They are alone, friendly, and uninformed, The curse of slavery is still upon them. Someone must take them by the hand; not to support them, but simply to help them to that work which will support them . . . The intervention of the national Government is necessary. Without such intervention, many of these poor people, freed by our acts in the exercise of a military necessity, will be left to perish.

Background: Mr. Charles Sumner, a Republican Senator from Massachusetts, spoke in favor of the establishment of a bureau that would provide educational privileges and aid to those in need. His support of the Freedmen’s Bureau Act was based on his belief that because the newly freed slaves received their freedom from legislative and executive actions, the federal government should also be charged with protecting and assisting them.

(3) Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 2nd Sess. 691-93 (1865) (Remarks of Representative Shenck)

[The bill] makes no distinction on account of color . . . it does not discriminate against whites; . . . it proposes to take care of all refugees, as well as all freemen, who may need the help of the Government . . . if we are to legislate on this subject, [we] would provide for refugees and freedmen, refugees of all colors as well as freedmen, in order that all shall have that temporary relief.

Background: Due to the controversy and number of objections to the original Freedmen’s Bureau Bill, the language of the Act and its proposed recipients changed. Representative Schenck from Ohio suggested these changes. Rather than limit support based on status as a freed slave, he proposed expanding aid to all refugees, freedmen, and destitute citizens. Refugees were considered to be African Americans, both freedmen and those freed prior to the Civil War, as well as southern whites feeling from secession. Whether citizens were destitute or not was determined by the Commissioner of the Bureau, who was charged with distributing benefits.

(4) Cong. Globe, 39th Cong, 1st Sess. 240 (1866) (Remarks of Senator Cowan)

[B]ut are we to alter the whole frame and structure of the laws, are we to overturn the whole Constitution, in order to get a remedy for these people? If they are put upon the same footings as white people, then they have the same remedies as white people; they have the same remedies that the honorable Senator has, or that I have, or that any other Senator has; and there is no necessity for this new jurisdiction, this new power that is to be invoked for their protection. We have been told that if a man was made free, and particularly if these colored people were made free, that that was all that was necessary; that then they would take care of themselves just like other people; and if the laws were framed generally so as to operate upon all people, they would operate upon them, and they would take advantage of it and protect themselves.

Background: Senator Cowan of Pennsylvania argues that because the Constitution already safeguards the rights of all American citizens, legislation allowing for special privilege and remedy should not be allotted to the newly freed slaves.

(5) Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 421 (1866) (Remarks of Senator Davis)

I move to amend the title by substituting this for it: a bill to appropriate a portion of the public land in some of the southern States and to authorize the United States Government to purchase lands to supply farms and build houses upon them for the freed negroes; to promote strife and conflict between the white and black races; and to invest the Freedmen’s Bureau with unconstitutional powers to aid and assist the blacks, and to introduce military powers to prevent the Commissioner and other officers of said bureau from being restrained or held responsible in civil courts for their illegal acts in rendering such aid and assistance to the blacks; and for other purposes.

Background: Senator Davis from Kentucky criticized what he believed to be the unconstitutional nature of the Freedmen’s Bureau during a debate to extend the Bureau for two additional years and to expand its powers.

IV. President Andrew Johnson, Veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill (February 19, 1866):

[Congress] has never deemed itself authorized to expend the public money for the rent or purchase of homes for thousands, not to say millions, of the white race who are honestly toiling from day to day for their subsistence. A system for the support of indigent persons in the United States was never contemplated by the authors of the Constitution. Nor can any good reason be advanced why, as a permanent establishment, it should be founded for one class or color of our people more than for another.

Background: President Johnson vetoed the bill to continue and expand the Freedmen’s Bureau both in February and July of 1866. The quotation below comes from his remarks after vetoing the bill for the first time. Johnson believed that control of education should be left to the states and smaller entities like private associations and individuals. Johnson also believed additional assistance to freedmen, who now as citizens had the full protection of the Constitution, went beyond the intent of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment, and was thus unconstitutional. [Note: President Johnson’s veto was overridden by Congress in 1866].